On Pacifism

By Prahlad Iyengar.

Editorial note: The author is a doctoral candidate in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and a recipient of the US National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. He has been barred from MIT campus until January 2026 for publishing this piece in Written Revolution in October 2024. We are republishing this thoughtful article out of support for Mr Iyengar and his freedom of academic expression. More information here.

The past year of genocide waged against the Palestinian people has led to protest around the world. At first blush, these protests may remind one of the protests against the genocide waged against the Vietnamese in the mid to late 20th century, or the protests against the South African apartheid state in the 1980s. It is true that the movement for Palestinian liberation today owes much to the liberation struggles of decades past, both in terms of tactics as well as overall strategy. However, many of today’s protests emphasize a principle which seems to have shaken the imperial American regime and its Zionist colony to their core. This principle is enshrined in international law, and can be stated simply as follows: an occupied people have the right to resist their occupation by any means necessary.

This principle is not new—activists during Apartheid South Africa, the Vietnam genocide, and plenty of other historical atrocities against the indigenous have supported the indigenous right to resist. But in today’s protest landscape this sentiment feels more prevalent. It has led many to support the axis of resistance, a loose coalition of Arab, North African, and West Asian regimes and groups which have defended Palestine and supplied the Palestinian resistance with material assistance, as they continue to challenge American and Israeli military actions which have thus far claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, according to even conservative medical estimates. That this ideological support for true resistance to imperial and colonial regimes is so instilled within the Palestine movement is a testament to the political education that has been achieved both in the decades since the American invasion and genocide in Iraq as well as in the past year of heartbreaking struggle for Palestinians. The movement has grown in this regard, and it will continue to grow.

But now, one year since the beginning of the accelerated phase of genocide, it is incumbent upon us all to remind ourselves of this commitment. That is to say, we must remind ourselves not just what that commitment means in the context of the resistance within the colonies, but also what it implies for our actions here in the imperial core. In our reflection, let us consider the methods that have defined the current movement for the liberation of Palestine.

Throughout cities across the world, we have been fortunate enough to observe a diversity of tactics, one of the signs of a healthy movement. In many major cities across Turtle Island, coalitions have formed under vanguard parties in order to lead city-wide protest events, including marches, rallies, and pickets. More specialized groups such as Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) and Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) have adopted specific targets (Elbit Systems and now Maersk, respectively) and have even recently achieved success in driving the Zionist-supporting companies out of town here in Cambridge, Massachusetts. National Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) has helped coordinate the development of SJPs across thousands of campuses, and during the spring of 2024, we witnessed an old tactic develop new wings at many universities: continuous reclamation of liberated zones. Some groups have taken things further during the “Summer of Rage” for Palestine, escalating to building occupations, property damage, destruction of surveillance and police equipment, and further tactics. Many of these examples have been documented under the media of Unity of Fields, formerly Palestine Action US, which is another reference to the axis of resistance calling for a unity of the fields on which they fight the Zionist and the American regimes.

Diversity of tactics, broad participation with targeted escalation, everything seems to be going swimmingly—except one major issue. To date, the movement on Turtle Island has seen virtually no success towards its main demands—ending the genocide, ending the apartheid, and dismantling the occupation. Fundamentally, a movement which is not nearer to achieving its goals one year later cannot be considered a success. Here, I argue that the root of the problem is not merely the vastness of the enemy we have before us—American imperialism and Zionist occupation—but in fact in our own strategic decision to embrace nonviolence as our primary vehicle of change. One year into a horrific genocide, it is time for the movement to begin wreaking havoc, or else, as we’ve seen, business will indeed go on as usual.

The analysis below is heavily influenced by Ward Churchill’s seminal essay “Pacifism as Pathology”. This discussion echoes mere fragments of Churchill’s argument and applies his analysis to the current mass movement for Palestine; I would highly recommend reading “Pacifism as Pathology” for a more thorough review of the history of pacifist movements and their ideological flaws.

Essential to this discussion will be the non-interchangeable use of the terms “tactics” and “strategy”. In layman’s English, these two terms seem reasonably close together, so as to be perceived identically; however, as we will explore, there is an essential difference between them. In the context of my argument below, the “strategy” of a movement refers to directional decisions made on the basis of underlying, principled commitments. “Tactics”, on the other hand, are directional decisions which, while remaining consistent with and working towards the underlying principles and goals of the movement, may deviate from their suggested course of action due in part to contextual conditions. Put succinctly: strategic pacifism seeks pacifism as an end in itself, whereas tactical pacifism uses pacifism as a means toward a goal without the exclusion of non-pacifist means.

A quintessential example of strategic pacifism, familiar to the American audience, is the Civil Rights movement, which relied heavily on the notion of “civil disobedience”. This mass movement saw broad participation and mass actions including sit-ins, boycotts, and marches, culminating with the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Along this path to liberation, many Black organizers in the American South braved extreme hardship and violence, including beatings, fire-hosings, and lynchings at the hands of racist citizens and police. Sacrifices were made, and people persevered through the struggle. A source of inspiration for this strategically pacifist movement, and one which its leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., often cited, was the nonviolent arm of the Indian struggle for liberation from British colonialism, led by Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi famously created a broad coalition across South Asia, including the indigenous Pashtun people of Afghanistan, though he was not immune to the casteism that the British used to indoctrinate the Indian population during their occupation. This nonviolent movement used similar strategies, most famously hunger strikes and the world-renowned “salt march” tax resistance campaign. South Asian nonviolent protestors were massacred in the thousands and routinely subjugated to inhumane treatment.

By no means am I suggesting that these pacifist movements were counter-revolutionary; in fact, their ideological commitments to pacifism can be seen as a fundamental rejection of the doctrines of violence against Black and Brown colonized peoples which followed from the status quo.

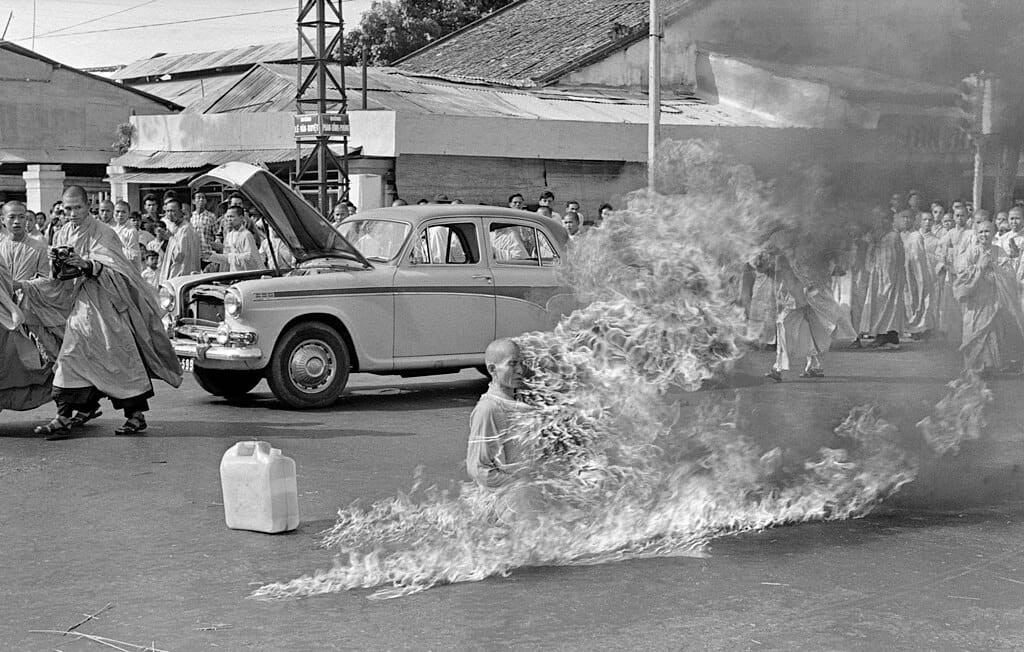

A shocking and historic example of tactical pacifism was the 1963 self-immolation of Thích Quang Đuc, a Vietnamese Bhikku (Mahayana Buddhist monk), in protest against the religious persecution faced by the Buddhist majority under the Catholic president Ngôình Diem, whose regime was propped up by the US government’s Indochina policy as a supposed bulwark against communism. This striking image was shared around the world and brought significant attention to the horrors that the US was wreaking upon Indochina. I call this tactical and not strategic pacifism because Thích Quang Đuc’s act was a response to the particular conditions of oppression his community faced, rather than an attempt to inspire a movement centered around ideological nonviolence. His last words are translated as:

“I call the venerables, reverends, members of the sangha and the lay Buddhists to organize in solidarity to make sacrifices to protect Buddhism”

– Thích Quang Đuc, [emphasis my own]

In the wake of the heightened awareness around the occupation of and ongoing genocide against Palestine by the Israeli settler-colonial state, this pacifist tactic has been repeated by several individuals, including Aaron Bushnell, a former US Air Force member who self-immolated in front of the Israeli embassy in the nation’s capital while on active duty. His last words were:

“I will no longer be complicit in genocide. I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest but, compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonizers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal.”

– Aaron Bushnell

The self-immolation of an active-duty Air Force soldier highlights the tactical rather than strategic act of such an act. While it could be claimed that Thích Quang Đuc’s monastic lifestyle reflects a personal commitment to nonviolence that indicates a strategic pursuit, Aaron Bushnell’s very vocation was antithetical to such a commitment. Both acts were done to draw attention to a particular struggle in a particular context, and both acts served the broader goal toward liberation without inherently excluding non-pacifist actions. Moreover, both acts are fully compatible with the simultaneous existence of armed resistance against the oppressor, and may even have been a tacit indication of support for such resistance.

Having defined these terms and even while acknowledging that both forms of pacifism are compatible with truly revolutionary praxis, I now seek to show that pacifism as a strategic commitment is a grave mistake in the context of colonial oppression. In fact, the theory of change I call for would see tactical pacifism take on a supplementary role within a cradle of widespread resistance. I will extend this analysis to the student movement, arguing that we have a particular responsibility to seek this diversification of our tactics due to our positionality.

Central to the concept of pacifist action is the intention of sacrifice. It is clear in the tactical examples noted above, but also evident in both Dr. King’s and Gandhi’s pacifist movements. In the latter cases, the sacrifice is inherent to the status quo – Black and Brown nonviolent protestors faced extreme suppression, imprisonment, and often lethal violence at the hands of the state. The centrality of sacrifice is key, for while pacifism requires nonviolence on the part of the activist, it does not impose any such restriction on their oppressor. Instead, its main vehicle for generating mass outrage and therefore spurring on its movement is by inviting that violence upon its adherents to hold up as a manifestation of the contradictions which run rampant in their oppressor’s world. Exposing these contradictions is crucial to dialectic change which drives revolution.

But not all pacifists are so committed. The most prominent proponents of pacifism tend to be organizers whose risk aversion and unwillingness to receive the violence of the oppressor truly drives their action. As Churchill notes:

“The question central to the emergence and maintenance of nonviolence as the oppositional foundation of American activism has not been the truly pacifist formulation, ‘How can we forge a revolutionary politics within which we can avoid inflicting violence on others?’ On the contrary, a more accurate guiding question has been, “What sort of politics might I engage in which will both allow me to posture as a progressive and allow me to avoid incurring harm to myself?”

– Ward Churchill, Pacifism as Pathology, p 73

This can be seen most evidently in the types of mass actions we have seen around the Palestine movement in greater Boston. A typical rally features

“hundreds, sometimes thousands, assembled in orderly fashion, listening to elected speakers calling for an end to this or that aspect of lethal state activity, carrying signs ‘demanding’ the same thing … as well as [highlighting] the plight of the various victims they are there to ‘defend’, and – typically – the whole thing is quietly disbanded with exhortations to the assembled to ‘keep working’ on the matter…" (Churchill, 73-74).

Churchill characterizes this aspect of protest as a “charade”, an example of political theater that does more to assuage the consciences of its attendees than it does to exact a cost from the entity which is enacting the very oppression they protest. He goes on to note an even more chilling fact:

“it will be noticed that the state is represented by a uniformed police presence keeping a discreet distance and not interfering with the activities. And why should they?... Surrounding the larger mass of demonstrators can be seen others–an elite. Adorned with green [vests], their function is to ensure that the demonstrators remain ‘responsible,’ not deviating from the state-sanctioned plan of protest” (Churchill, 74).

He observes that those

“who attempt to spin off from the main body… [f]or some other unapproved activity are headed off by these [vested] ‘marshals’ who argue–pointing to the nearby police–that ‘troublemaking’ will only ‘exacerbate an already tense situation’ and ‘provoke violence’ thereby ‘alienating those we are attempting to reach’”(ibid).

When I first read these words, I felt attacked and betrayed. Over the past year, I have not only engaged in but even helped plan this very charade. In doing so, I had not intended to dilute my political message or undermine the very value of truly revolutionary pacifist protest. And yet I found myself questioning the intention, direction, and purpose of my actions, reconsidering the types of actions I had encouraged, or tacitly discouraged, by engaging in protest in this way. But surely, I thought, our willingness to put our bodies on the line and even be arrested for our cause would stand apart? After all, as we know too well, MIT and the city of Cambridge have sicced their fascist militias, the police, on student protestors at plenty of our actions, especially in recent months.

Alas, Churchill has anticipated this objection and issues a cutting response. Just a page later, he analyzes what he calls “symbolic actions,” which are a meager attempt of movement organizers to salvage a “credible self-image as something other than just one more variation of accommodation to state power” (Churchill, 75) via so-called “militant” actions. He notes that “the centerpiece of such activity usually involves an arrest, either of a token figurehead of the movement (or a small, selected group of them) or a mass arrest of some sort.” These actions are usually preceded by Know Your Rights or arrest training to ensure that no participant receives escalated charges or injuries, which would inconvenience both them as well as the legal-carceral state. He lists the following types of “symbolic actions”: sit-ins in restricted areas, “stepping across an imaginary line drawn on the ground by a police representative” (Churchill, 76), refusal to disperse, and chaining oneself to the doors of a public or private building. In the case of self-proclaimed “militant” actions, protestors will also “go limp” so as to maximally inconvenience the arresting officer, usually under the watchful eye of a legal observer who notes any uses of excessive force for the subsequent trial process which ends in pre-arraignment deals and light charges like trespass or disturbing the peace. Painstaking care is taken to ensure that the protestors do not receive charges such as resisting arrest or assault and battery of an officer, and even if our heroes face these charges, they are almost always due to police misconduct and a broken penal system. As for the charges,

“It is almost unheard of for arrestees to be sentenced to jail time for the simple reason that most jails are already overflowing with less ‘principled’ individuals, most of them rather unpacifist in nature, and many of whom have caused the state a considerably greater degree of displeasure than the nonviolent movement, which claims to seek its radical alteration”

(Churchill, 77).

I want to make something clear. I am not trying to trivialize the level of trauma that being arrested at a protest has caused our community, nor am I suggesting that the experience of police violence is somehow illegitimate. Members of our community have been brutally arrested. We have faced an excessive use of force even without arrest. We have also faced profiling, intimidation, and threats by the police and by Zionists on campus. All of that is real. MIT’s willingness to subject its students to MIT Police Department (MITPD) violence, and MITPD’s reliance on Cambridge PD to do its dirty arrest work, needs to be confronted head-on and stopped in its tracks.

And yet Churchill’s message is clear: despite the suffering we have faced at the hands of the state—and its institutional extension, the administration—our actions are in some sense part of the state’s inherent notion of protest. Yes, oppression breeds resistance, but resistance of this form is already accounted for within the state’s logic—we are, in a sense, culturally pacified, not willfully pacifist.

During my arrest at the Scientists Against Genocide Encampment, I recalled my first experience with arrest, when I witnessed a Black man get tackled while walking between platforms by at least six officers and put in several limb-locks and a headlock, all while his partner sobbed in hysteria next to him. He became in that moment a thing tackled, a thing restrained, no longer in possession of his humanity due to the criminal robbery of the latter by the fascist state. I thought I was lucky to not have experienced that level of violence, although I had experienced some on various occasions. But after reading “Pacifism as Pathology,” I have come to realize that this was not luck—it was, in some sense, by the design of the state. For despite my protest and despite my staunch opposition to the state through my actions, I was still a cog in its system, merely the rust which develops on the gears in order to beckon for more grease. I had not clogged the system—I had fed it.

During my time in holding, I and others who were arrested with me met a man—a kid, really—who was brought in a bit disheveled and clearly sleep-deprived. When he awoke after hours in the cell, he told us that he had been on the streets since he was sixteen, after being kicked out by his abusive stepfather. He had spent the next three years living in shelters, sleeping on bus stop benches, and squatting in houses—he quickly learned which were the ones that were abandoned and would remain unchecked for a time. Before we spoke, one of the guards came by and it was clear they knew each other—the kid asked for a meal, and the guard said he would get it. He told us that these officers would play games with his life—they knew he was on the street, would let him stay out for days or weeks at a stretch, then find him in whichever abandoned property he had found for shelter and arrest him. They wouldn’t charge him with much, and he’d be out without bail, only to repeat the cycle over and over and over. Suffice to say, the guard never came back with his meal.

As people of conscience in the world, we have a duty to Palestine and to all the globally oppressed. We have a mandate to exact a cost from the institutions that have contributed to the growth and proliferation of colonialism, racism, and all oppressive systems. We have a duty to escalate for Palestine, and as I hope I’ve argued, the traditional pacifist strategies aren’t working because they are “designed into” the system we fight against. The state has had decades since the Civil Rights movement to perfect its carceral craft, and it has created accountability pathways that ignore strategically pacifist movements—it is happy to let us back out into our worlds, patting ourselves on the back for our actions, because we have already committed to compliance. Strategic pacifism commits itself to pacifism as an end in itself, and the state has used that commitment to monopolize its control of violence.

As students, even when committed to pacifist strategy, we still feel like we are sacrificing. This is primarily due to the institution’s heavy reliance on discipline and sanctions. Many of the US citizens in our community understood this subconsciously last year—if we put aside for the moment the existential question of police violence and brutality (which I recognize that many of us fundamentally cannot put aside owing to our overpoliced identities, but bear with me) and consider merely the on-paper consequences of arrest vs. suspension, we would certainly recognize that institutional discipline is a more worrying prospect than an arrest for the lesser charges we have come to expect. So when we face discipline, including possible suspension or expulsion, we are risking something important which is acknowledged by our supporters in the community, both local and global. But although this is a real sacrifice, it does not change the content and cost of our actions. Instead, I believe that this extra layer of sacrifice is dangerously illusory. The material and social value of a degree from MIT is derived from whatever legitimacy we, as a broad society, give to the institution. The potential delay or loss of the degree is only a sacrifice insofar as MIT, and academia as a whole, have created their own market of scarcity and elitism wherein the value of this degree is high. If we remove that degree and strip away the structural elitism, our actions may become exactly what Churchill suggests: a charade.

That isn’t entirely fair, perhaps because I have yet to acknowledge that MIT is itself part of the state. MIT is a military contractor. MIT does research for genocide. MIT contributes to the fascist vision of American empire; we’ve developed radar technology for war, WiFi-based object detection for policing, and spun out Raytheon. We are the state, and to the extent that our Coalition can exact a cost at MIT, we can claim that we are exacting a cost to the state.

But we also exist in a microcosm of the real community of Boston and Cambridge. We students will only remain here for four to eight years before leaving the community, having used its resources and land for our labor, without a thought for the thousands of Black folks who have been economically displaced by rent hikes driven by MIT’s expansion and gentrification nor for the indigenous communities from whom all of this land was stolen and who still need restitution via land ownership. As we continue to organize for Palestine, our actions draw the police and prime them for the beatings they so desire to mete out yet cannot on “innocent and peaceful” students. So they will turn to the real community and exert their authority over them. As we fight for food security on campus, we ignore the deep food insecurity in Roxbury; as we create networks of inter-university solidarity, we leave out key members of the community whose efforts could use our support, and vice versa. As we get arrested and require bail or jail support or community help, we pull those resources from the community of activists in Boston and leave the community under-resourced and over-policed. And as we commit to strategic pacifism, we create a false contrast which endangers local community members whose actions do not conform to the “designed-in” models of protest or being, thus making them targets for repression and oppression.

One year into the accelerated phase of genocide, many years into MIT’s activism failing to connect deeply with the community, we need to rethink our model for action. We need to start viewing pacifism as a tactical choice made in a contextual sphere. We need to connect with the community and build root-mycelial networks of mutual aid. And we must act now.

Comments ()